The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the vulnerability of smallholder farmers to unexpected crises. The crisis disproportionately impacted women, leading to negative consequences on household gender and nutrition outcomes. The pandemic exposed agricultural institutions to risks that impacted day-to-day operations and long-term impact, forcing institutions to adapt to the difficult environment on the ground.

While COVID-19 is a unique situation, other crises such as political conflicts, droughts, and climate-related events are increasing, and will likely cause further shocks in the near term. With this in mind, the pandemic highlighted the need for agricultural institutions to adapt their strategies during crises in a gender and nutrition-sensitive way.

Impacts on farmers and on the agricultural institutions who support them

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to unfold, emerging research is unveiling the impacts of the crisis. According to the agricultural institutions in IGNITE’s network, and complementing existing research, the pandemic affected agricultural households through:

- Decreased market access, both for buying and selling.

- Missed income opportunities, when people cannot travel for seasonal labor or cannot sell their agricultural products due to lockdowns and restrictions.

- Declining nutritional quality in terms of quantity and variety.

- Strained household dynamics between men and women.

- Reduced farm-level productivity, due to decreased access to inputs such as farm labor, seeds, or fertilizers.

- Increased emotional burden and stress.

The shock forced agriculture institutions to adjust how they did their work (e.g., less in-person contact, new lines of communication, physical distancing), the goals of their programs, and what work could be implemented on the ground.

Learning from experience

The IGNITE team reached out to its network of clients to ask how agricultural institutions coped with these challenges from a gender and nutrition perspective. Different teams reacted in different ways, some focusing on gender-sensitive issues, others more on nutrition. A common theme was that each client had to adapt and quickly revise their priorities.

The IGNITE team published a case study highlighting the ten lessons learned during this process. These lessons can be categorized in three phases of a crisis cycle.

Before a Crisis: Deliberate Preparation

Where agricultural institutions can prepare to react in a gender and nutrition-sensitive way during a crisis by dedicating time and energy to advance preparation.

1. Integrate critical gender & nutrition concepts into habits and rhetoric. A focus on gender and nutrition ‘mainstreaming’ creates advance buy-in that ensures gender and nutrition issues remain priority.

2. Build capacity of program staff around gender and nutrition. Staff prepared with best practices around gender and nutrition can ensure responses are sensitive across each program and area of expertise.

3. Build and leverage key relationships. Public and private sector actors can leverage networks to reduce risk in programmatic activities.

4. Develop robust data systems. Have a healthy Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) system in place before a crisis, with appropriate gender and nutrition indicators.

5. Develop a Crisis Action Plan. The organization-level general emergency plan provides overall safety and communication guidance while preparing for gender and nutrition-sensitive responses.

During a Crisis: Thoughtful Reaction

Where agricultural institutions can engage in thoughtful reaction to ensure gender and nutrition-sensitive adaptations are supporting staff and beneficiaries through the crisis.

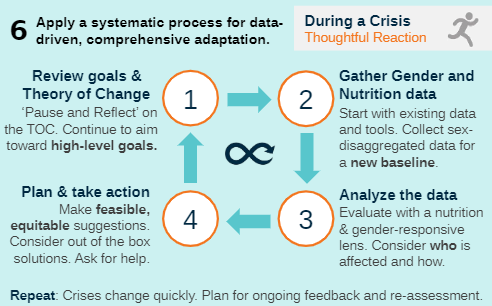

6. Apply a systematic process for data driven, comprehensive adaptation. This includes reviewing the goals and the Theory of Change; gather data for new baselines; analyze the data through a gender and nutrition-responsive lens: consider who is affected and how; and plan for feasible and equitable suggestions.

Tanager, Laterite and 60 decibels have created a one pager to summarize lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic.

After a Crisis: Continued Care

Where agricultural institutions can optimize the recovery process and further promote gender and nutrition-sensitive outcomes.

7. Remember that recovery takes time. Smallholders will be recovering for years, so remain gender and nutrition-sensitive as time use, total wealth, and income streams are now distorted.

8. Look for emerging opportunities to promote high-level goals. As market dynamics, like pricing, labor sources, and inputs availability, will have shifted in the crisis, seek out and take advantage of emerging gaps.

9. Learn from the crisis. ‘Pause and reflect’ to understand what worked, what did not, and why. Then update crisis plans, collect data, and plan resilience into programs.

10. Advocate and raise awareness. Help governments and partners understand consequences of crisis-related policies and effects on smallholders and market systems.

This blog post was written by Tessa Ahner-McHaffie and John DiGiacomo, Research Associates at Laterite Kenya, and is based on a case study prepared in the context of IGNITE.

IGNITE (Impacting Gender & Nutrition through Innovative Technical Exchange in Agriculture) is a five-year investment implemented by Tanager, Laterite, and 60 Decibels to strengthen African institutions’ ability to integrate nutrition and gender into their way of doing business and their agriculture interventions.

Read the full case study or the one-page summary.