This blog summarises highlights from our latest research synthesis (also translated into Kinyarwanda) focusing on Rwandan secondary school teacher attitudes, training and retention, as well as student learning outcomes, when schools reopened after the COVID-19 closures. The publication also shares implications for policy and future research based on the findings.

The data was collected after schools reopened in late 2021 by Laterite and the REAL Centre at the University of Cambridge for the Leaders In Teaching programme. This five-year programme is funded by the Mastercard Foundation to improve the quality of teaching and learning in Rwandan secondary schools, with a focus on science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects.

1. How did COVID-19 related school closures impact student enrolment and teacher turnover?

- Student enrolment increased after schools reopened, especially in Secondary 1 and Secondary 4.

- There were modest learning gains, though we can’t compare these with learning gains to be expected during the same period in a normal school year.

- Boys still slightly outperform girls in terms of average numeracy assessment scores.

- After schools reopened, most STEM teachers (94%) returned to teach their classes.

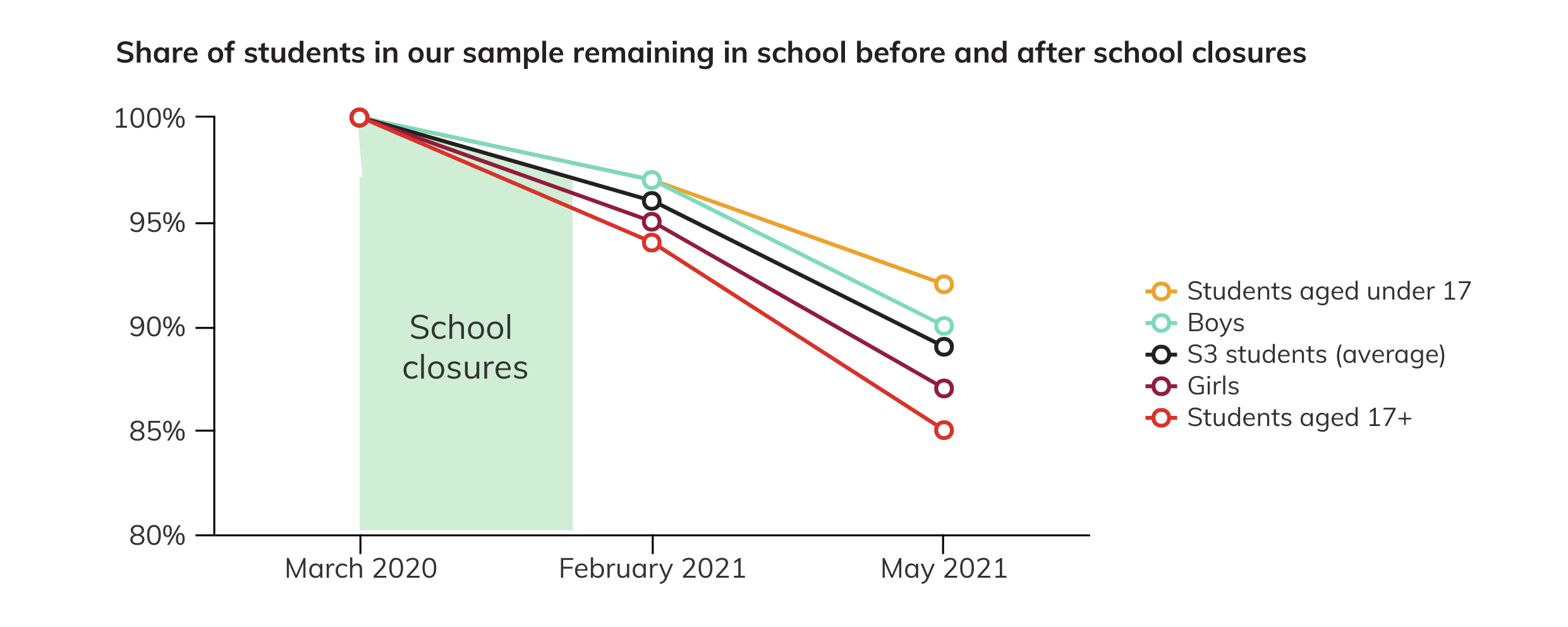

- Fewer Secondary 3 students remained in class as the school year progressed. Girls and overaged students (older than 17, which is above the expected age for Secondary 3) were the least likely to remain in class. Compared with those from the same time period in a normal school year (using data from the MINEDUC Statistical Yearbook 2021), these trends appear to be similar to that of an average school year.

What can decision-makers do to support student enrolment and progress through the education system?

- Support students at risk of dropout with resources to remain in school and complete their studies, for example by providing remedial learning.

- Continue to monitor student dropout and learning – especially among girls and older students, and students from lower-income families – to understand the long-term impacts of school closures on student attendance and learning over time.

- Increase efforts to train school leaders in gender-sensitive teaching practices, which could contribute to closing the student performance gender gap.

2. How did continuous professional development (CPD) of school leaders and STEM teachers change compared to before school closures?

- Most school leaders reported receiving training on at least one topic in the 12 months before school closures.

- Female school leaders were under-represented both as school leaders (only one in five school leaders is female) and as recipients of in-service training.

- The focus of CPD shifted after schools reopened. The leading focus of training before school closures was the competence-based curriculum. After schools reopened, the focus of training for STEM teachers shifted to STEM and ICT topics, as well as other topics such as lesson planning, innovative assessment, remedial learning, and maintaining safety from COVID-19. For school leaders, the focus shifted to coaching teachers and other topics such as developing strategies for remedial and catch-up learning, managing student dropout, school planning, and managing resources.

- Access to computers declined for STEM teachers after schools reopened, especially for female teachers.

How could decision-makers improve CPD provision for STEM teachers and school leaders?

- Enable female school leaders to attend CPD, for example, by adding more flexibility to CPD schedules and providing training closer to where they live so that they can participate.

- Carry out a broader capacity and training needs assessment to improve the targeting of CPD across different groups and schools, especially among less-resourced schools. At the same time, enable educators at different career stages to decide which CPD they will take.

- Increase access to computers or tablets for all teachers as well as training on how to use them in a classroom context.

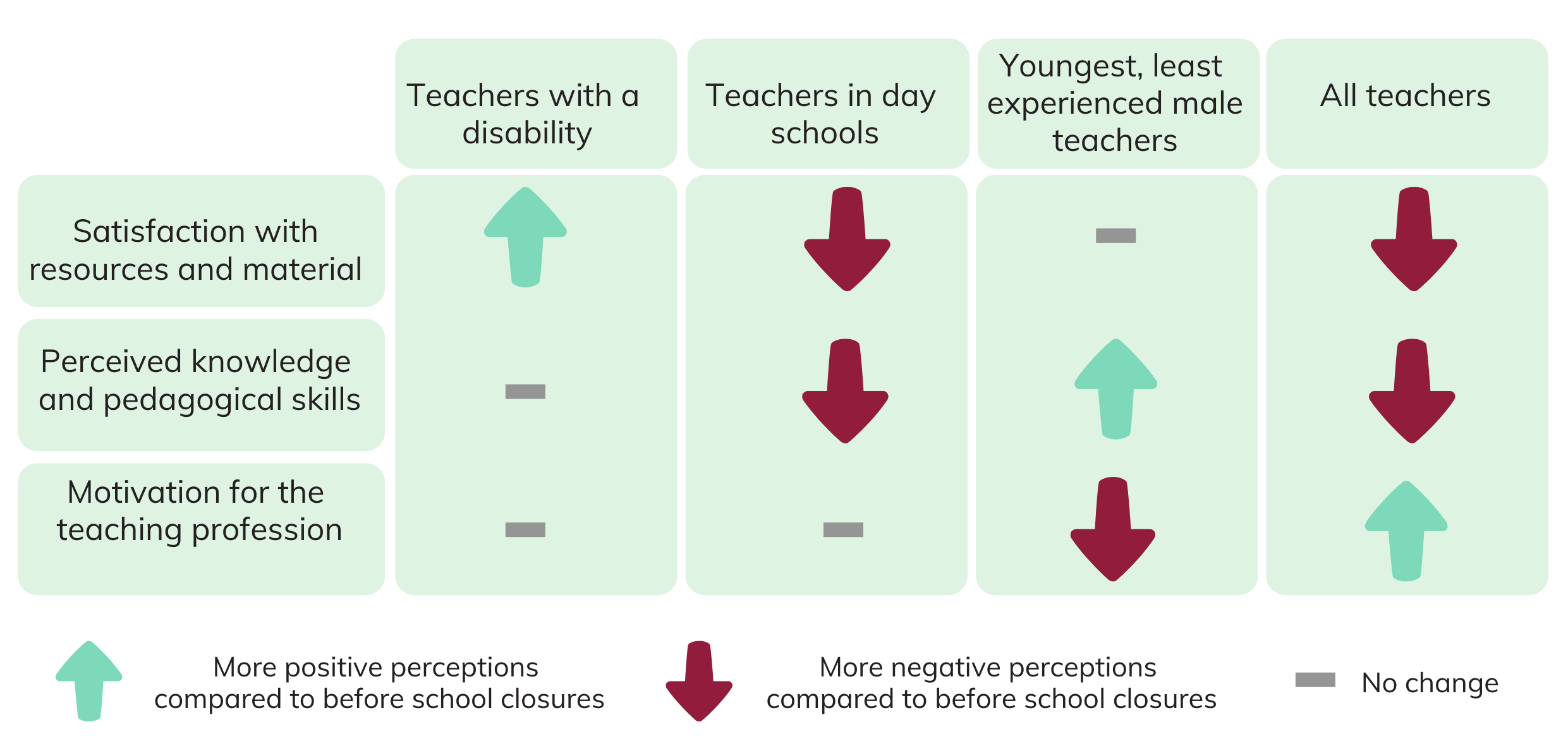

3. How did STEM teachers’ perceptions of teaching quality change after schools reopened, compared to before school closures?

- STEM teachers’ perceptions of teaching quality changed after schools reopened.

- These views differed based on type of school and teacher characteristics.

In response, programming staff and policy-makers could:

- Tailor teacher training plans in areas where perceptions have become more negative, such as teacher knowledge and pedagogical skills, satisfaction with resources and materials, and motivation for the teaching profession among the least experienced teachers. Teachers with a disability should not be left behind in these efforts.

- Continue to focus efforts, in terms of resources, infrastructure, and teacher training programmes, on less resourced schools.

- Explore opportunities to mentor or train newer teachers, to address their lower motivation compared to before the pandemic.

The findings of the ongoing research for the Leaders In Teaching programme are being shared with policymakers and other education stakeholders as the research emerges. This includes the teachers and school leaders who participated in the research. Further data was collected in 2022 and 2023, and the findings will be published soon.

This blog was written by Laterite and the REAL Centre at the University of Cambridge. It was originally published on the UKFIET website.

Image credit: VVOB. Teacher Berthe Musabyeyezu groups her learners into smaller groups to increase their participation.